My Grandma’s escape from death thanks to poker, and what it taught me

My mum’s mum was always fun. She was blind by the time I remember her, but just pushed through life regardless, generally getting away with things. She would walk straight out into four lanes of traffic assuming it would stop for her (and it did), and go out to the shops alone, confident she’d find someone along the way who’d walk her home (which she did). When I went to stay with her as a boy, mum would tell her not to give me too much food or let me watch too much TV. She would agree, all diligent and serious, then put me in front of the TV for the whole night, frying rounds and rounds of sausages until I couldn’t eat another thing.

I knew her as an elderly, sweet, occasionally difficult old woman, whom we all loved, and who occasionally drove us mad.

She was born in Poland. Her name was Rhoda. Her birthday was the 1st of January.

Her family came to the UK in the 1920s, after a boat journey from Poland to Buenos Aires. At the time, Argentina was enjoying an economic boom, and to address labour shortages they advertised for Eastern Europeans to move over there to farm land. Somehow, my great-grandfather, a tailor from Poland, took his family to Argentina. The story goes that they loved it. He was, they said, a playboy and gambler, and Buenos Aires was a city full of fun and life. But his wife hated it, and missed her hometown back in Poland, so they set off back home. The family stories I grew up with were that they took a ship back to the UK, on the way to Poland. On the boat great-grandpa lost everything playing poker. They arrived in England destitute, and were not able to afford the passage back to Poland, so they settled in London.

He set up a tailor’s shop on St Johns Wood High Street (not the glistening wealthy road it is now), and grandma worked as a waitress, and during the war was a nurse. She told me stories of stepping through the broken glass during the Blitz, looking for the wounded.

Recently, papers started to surface which gave me some clues to dig deeper into this story. Also, now everything is on Google, I was able to find out incredible details from these few clues. But also the story took an unexpected turn, one which I felt resonated with the world around me now. Despite having been dead many years, grandma taught me some things recently, looking back into her stories and shared memories.

The papers I found documented their voyage to England. They confirmed that they arrived in 1929 from Buenos Aires, on the S.S. Gelria, a Dutch liner. It was the height of luxury in First Class, but my family would have been travelling Third Class, in the bowels of the boat. There are no photos or accounts of that part of the ship. Amazing, though, to find postcards of the boat that brought them to England.

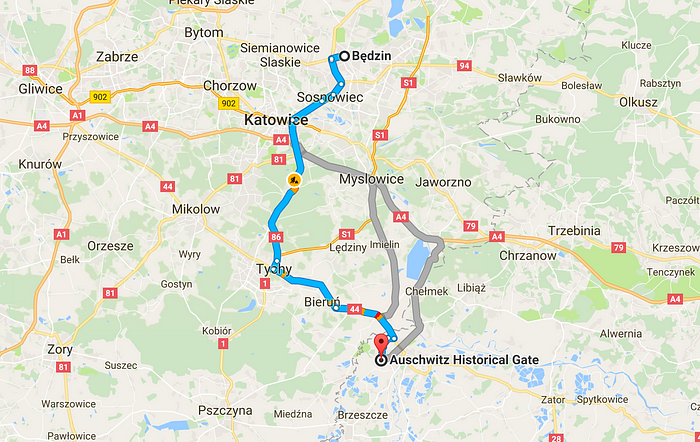

I knew they came from near Krakow in Poland, but the documents also pinpoint exactly that great-grandpa was from Bedzin, and great-grandma from Sosnoweic. These towns are near Katowice, and near Krakow, so the story was basically correct. In fact, Sosnoweic is just 10 minutes by train from Katowice, 1:50 from Krakow by train, and a 2:30 train ride from Auschwitz.

I remember my grandma once telling me how one of her relatives who remained back in Poland went on the run from the Germans, hiding in a forest with her little son. They were caught by German soldiers, who pulled his trousers down. When they saw he was circumcised, they shot them both. I never wondered how she knew this story, but presumably somebody must have escaped to tell it.

But only now, when I found these papers, did I realise that the towns they left, and failed to return to because of great-grandpa’s poker habit, actually became extensions of Auschwitz. The Jewish population in that part of Poland was almost entirely wiped out.

I was always told that getting stuck in England, where they started off as ‘inmates’ in the ‘Jews’ Temporary Shelter’, had probably saved their lives. But finding out now that they were basically trying to get back to a town near Auschwitz was chilling. If they’d made it back to Poland in 1929, they would not have survived the war. Also the dates. They arrived in England in 1929. I never really took on board that it was only 15 years later that everyone they had ever known back in Poland, literally everyone they had ever met, passed on the street, smiled at, not to mention everyone they were in any way related to, was killed. This was not a generation later, this was their now. This was their world, their neighbours and friends.

Two things struck me. Firstly, nobody ever talked about this. Apart from that one story about the boy in the forest, which I heard only once, nobody ever talked about the fact that everyone they had known before leaving Poland had been killed. But the other thing is that in the whole story of them leaving, going to Argentina, coming back to England, they never once used the word ‘refugee.’

I always heard this story as one of japes and adventures. What fun it was to go to Buenos Aires, how nice it was to end up in London. I heard the fun stories of grandma and her sister going back to BA as young women, hanging out with rich Argentines, partying on yachts, of great-grandpa playing poker, being dapper, sitting talking Yiddish in cafes in North West London. It was all quite fun.

In the papers, she is variously called Rosa, Rhoda, and other Polish variants on the name. Her father is Tobias, Tobiasz, Theodor (?), and more. It’s clear some of the papers her sister used to move back to Argentina were forged, and her brother’s records in the UK are locked shut for 100 years under a rare Home Office clause. We think this is because he was born in Argentina, and years later the Argentine army tried to arrest him to draft him into their army — locking down his immigration records means they would not be able to prove he’d been born there. Clearly this is the story of people on the run, afraid, trying to find a safe haven. People don’t change names and forge papers when things are going well.

And then I found myself wondering if she really was born on the 1st of January, 01/01. It seems more likely that was a lazy immigration official filling a form for some Poles who didn’t speak English, or perhaps for some Poles who had no idea what date she was born.

In fact, now I look at the story with facts and history to explain it all, they left Poland towards the end of a very unstable period, with pogroms and a shift in attitudes towards Jews in Poland, which for most of its history had been unusually friendly towards its Jewish population. And they ran half way around the world and back, initially looking for a safer but also economically more positive place to live, and ended up in England, broke and in danger. They were not the fun loving economic migrants of the stories from my childhood, but in fact refugees who would certainly have been killed had they returned home.

Looking at the refugees of today. I wonder how many call themselves refugees. I wonder how many descendants of today’s economic migrants will look back in 2 generations and realise they were actually refugees. I wonder how many of these people are at risk from things we can’t yet imagine, yet to happen in the near future, to them and their families, and friends back home.

My family were lucky to be accepted into England. Their journey was far harder than I ever imagined. My sweet, blind grandma; a funny little Jewish woman from North West London, was actually a survivor, hard as nails, who had travelled from Poland to Argentina, and back to London, and was trilingual as a result. If she’d had any childhood friends back in Poland, they’d all been killed in the Holocaust. All of her extended family had been killed, and her parents must have eventually known that everyone they had ever known was dead. They hid it well, pushed through and made their lives work. They carried a lot of baggage, never talked about any of it. I am sure today’s refugees and migrants are no different.